Family

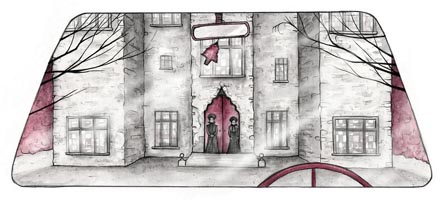

Here's a bonus short story of mine that you might enjoy. My thanks to Laura Trinder for her gorgeously sinister illustrations. (Note: You can click on any of the images to see a bigger, more detailed version.)

Story © Sam Enthoven / Art © Laura Trinder, 2015. All Rights Reserved.

'Julia,' I said, trying for a smile, 'all families are weird. How bad can yours possibly be?'

Julia didn't smile back. 'They're not just weird, Ali. They…' She bit her lip. 'They can be dangerous.'

I gave her a level look. Dangerous. That was a new one.

We'd only been together six months, but already I knew Julia was the best thing that had ever happened to me. When she'd told me that her parents wanted to meet me and had invited us to come and spend the weekend at their house in the country, I'd been delighted. I wanted to do the right thing. I wanted Julia's family's blessing and acceptance. The biggest obstacle to that, to my surprise, had turned out to be Julia herself. As the date of the visit approached she'd become increasingly edgy and anxious. Now, pulling over just before the turning that led to her family's house, she'd stopped the car and told me they were "dangerous."

'Julia,' I said, 'I love you. I want to share your life with you - all of it. So: are we going in? Or are we turning around and going home? Because if your folks find us at the top of their drive then we're the ones who are going to look weird, don't you think?'

'This is a mistake,' said Julia, putting the car in gear.

The old grey stone house stood alone in the middle of wide open fields. By the time we reached it two women were outside the front door waiting for us.

Even though Julia had told me to expect it, the ladies' appearance was still a surprise. They wore identical plain black full-length dresses with sleeves that came down to their wrists. Black bonnets covered their hair and framed their faces. When Julia got out of the car they didn't move to hug her or kiss her, they just stood there watching her.

'My daughter,' said one - making me blink. 'We have missed you.'

'Mum.' Julia nodded. 'This is Ali. Ali; Mum.'

If the theory that a person can tell what their girlfriend is going to look like when she's older by looking at her mother was true, I could count myself a lucky man: Mrs Stephens looked terrific. Her orange-brown eyes had the same dancing glint of green as Julia's. The tiny laughter lines I now saw at their corners – the one sign of age I could find on her face – only added to her air of poise, grace and authority.

'Mrs Stephens,' I said, sticking out my hand. 'Brilliant to meet you.'

She didn't move.

'Our mother means no offence,' said the other black-clad lady, stepping forward. 'It is only that in our family we keep physical contact to a minimum.'

'This is my sister Jennifer,' said Julia.

Jennifer gave me a wide smile. I noticed a cute little brown mole above the corner of her lip.

'Hi,' I said. Then I remembered to let my hand drop and looked back at Mrs Stephens. 'Er, sorry.'

'Please don't be,' said Julia's mother. 'Many of our habits are going to seem strange to you. But Jennifer spoke truly: you are most welcome, Ali.'

'Thanks,' I said.

'Please follow me.' Mrs Stephens and her two daughters turned and set off.

"Strange" was right: already I was boggling a bit, but I fetched our wheeled suitcase from the boot of the car and followed as best I could, lugging it behind me across the gravel. I clunked up the steps, walked through the door – and there, standing waiting in a large entrance hall at the foot of an impressive winding staircase, were all the rest of Julia's family.

There were something like thirty of them. No one looked younger than Julia and Jennifer and myself but there were plenty who were older. The women all wore the same plain black dresses as Jennifer and Mrs Stephens – even (I noticed) the lady in a wheelchair with a blanket across her knees. The men wore equally plain black suits, with white shirts buttoned to the neck. Apart from their clothes two more things struck me about the Stephenses: they were all silent, and they were all looking at me.

'Hi everyone,' said Julia. 'Meet Ali. Ali, meet the family.'

I pasted a grin across my face, took one hand off the suitcase and gave a cheery wave. 'All right?'

The silence that followed lasted for three whole seconds: I counted. There was plenty of time for me to think about how my voice had come out higher than usual, about how How do you do? or even just plain Hello would definitely have been classier than what I'd said, and about how I'd never waved at anyone in quite that idiotic way before, never mind a group of people I was trying to impress.

'You're in the red room, Ali,' said Mrs Stephens. 'Julia will show you the way.'

'You were right,' I told Julia as soon as I'd shut the door behind me. 'Maybe this wasn't such a great idea.'

The red room was pretty amazing. There was a real four-poster bed. The velvet curtains matched the rich, swirling pattern of the wallpaper.

'We can't leave now,' answered Julia in a hollow, flat voice that made me stare at her. 'They would just come after us.'

'All I meant,' I said, frowning, 'is that they're going to think I'm an idiot. In fact they probably think that already.'

'Believe me,' said Julia, 'if tonight goes wrong, having the family think you're an idiot will be the least of our problems.'

'Julia,' I asked, 'what aren't you telling me? What's going on?'

Julia looked at me, bit her lip again – but shook her head.

'Nothing,' she said. 'Just an awkward family gathering – I hope.' She shivered. 'Listen, do you mind staying in here for five minutes while I go to my old room and get changed? I think our chances will be better if I show them I'm still prepared to wear the family weeds while I'm here.' She stepped close to me and surprised me with a quick, warm kiss on the lips. 'Five minutes? Then I'll see you down there?'

The door clicked shut.

As I sat on the bed to wait, the small but insistent part of me that I'd been trying to shush and suppress these past few weeks finally escaped and made its feelings clear.

I'd pushed Julia into accepting her family's invitation and bringing me here, but suddenly I couldn't remember why. I didn't care a hoot about her family really: all that mattered was Julia and I, the way we felt about each other. At that moment I allowed myself to wish that we'd stayed away, having fun, just the two of us or with our friends, instead of having come all the way to the middle of nowhere so I could make a fool of myself trying to impress her weird relations.

Before heading back to the party I checked my phone: no signal, no coverage, no way to communicate with the world outside the family. That figured.

'This is cousin Constance,' said Julia. Another black-clad lady inclined her head until all I could see was the top of her bonnet. I realised I'd already lost track of who was who.

The Stephenses had formed into a sort of funereal chorus-line. Julia, now also wearing the family black, was leading me along making introductions. As well as cousin Constance I'd met cousin Rafe, cousin Jemima, cousin Malcolm, cousin Enid, cousin Jerome, cousin Mary, cousin Caleb, cousin Howard and cousin Katherine: there were more, but those were all I'd remembered before my brain hit maximum capacity. The line of Julia's waiting relations extended all the way through a set of dark wooden double doors and into the dining room.

But just when I thought that everyone in the Stephens family was going to be referred to as "cousin whatever" we reached the last two members.

'This is Grandmama,' said Julia, indicating the old lady in a wheelchair I'd noticed before. 'And this,' she finished, 'is Father.'

'A pleasure,' said Julia's dad, stepping forward, taking my hand in his and crushing my knuckles into powder while staring straight into my face to see how I would react. So much for minimum physical contact.

Mr Stephens was maybe three centimetres taller than me, with thick arms and a meaty red face. His nostrils were so full of steel-grey hairs that they looked like they'd been stuffed with wire wool. The faces of the rest of the family were pale; the house around me was cold. Mr Stephens radiated heat.

'Hi,' I managed. 'Great to meet you.'

'You're over here, Ali,' said Mr Stephens, releasing me and indicating the seat to the left of the head of the table. 'You'll be beside Grandmama, opposite me. Please: sit.'

Resisting the urge to rub my mangled hand until it was safely hidden under the table I did as I was told – and noticed something odd. At every place at the long black dining table except one, a bowl of soup was already waiting. Beside each bowl there was a plain silver spoon. At my place there was a knife and fork – and nothing else.

Feeling thoroughly self-conscious and confused I waited as the Stephens family filed in and took their places around me. After a moment I reflected that the soup thing did, in fact, make a strange kind of sense. Soup was all Julia ever ate. Her unusual eating habits were one of the first things I'd had to get used to when we'd started going out. Now perhaps I was seeing where she'd got that from. Maybe soup was all her family ate, too. But even if that was true, I couldn't help wondering: why hadn't I been given any soup?

'Don't concern yourself, Ali,' said Mr Stephens, obviously enjoying having guessed what I was thinking. 'Mrs Stephens has prepared you something special. And here it comes!'

The dining room doors swung open and in came Mrs Stephens carrying a carving board on which rested a steaming roast chicken. Julia's sister Jennifer followed behind with a tray containing dishes of vegetables and potatoes and a small jug of gravy: all these and the chicken were set down in front of me. Then, while Jennifer and Mrs Stephens took their seats, Mr Stephens reached into the drawer of a black lacquered sideboard and produced a two-pronged fork and a long, gleaming knife.

'Would you like a leg to start with, Ali?' he asked, still smiling. 'Or are you more of a breast man?'

'A leg, please,' I said, carefully.

'Vegetables? Potatoes? Gravy?'

'Thank you.' The food was heaped on my plate. It smelled wonderful.

'Please, Ali,' said Mr Stephens, as I waited for him to sit, 'eat. And tell us how it tastes.'

It was an odd thing to say. But I realised that Mr Stephens wasn't the only one who wanted to know what my meal was like: none of the thirty people now sitting at the long dining table was showing the slightest interest in their soup. The entire family was looking at me and my food with a kind of eagerness in their eyes.

Obediently I picked up my cutlery. With thirty pairs of eyes watching me I cut myself a small piece of chicken, loaded the fork with a little potato and a few peas, pushed the forkful into my mouth and began to chew. I swallowed as quickly as I could without choking.

'Absolutely delicious,' I said.

Wistful smiles spread around the table.

'We are glad,' said Mr Stephens. He sat and reluctantly picked up his soup-spoon; the rest of the family did the same. 'Please,' he added, 'enjoy the chicken. Anything you do not eat will only go to waste.'

I stared at him as the air around me filled with the clink of spoons against bowls.

'You don't mean this whole chicken is just for me?' I asked.

Mr Stephens smiled again. 'That is correct.'

'Isn't anyone else going to have any?'

Mr Stephens' smile faded a little. 'Our family,' he explained, 'has certain… digestive peculiarities. It's a delicate subject, particularly for the table, but we are, alas, unable to eat solid food.'

I turned to Mrs Stephens. 'You cooked this for me especially?'

Julia's mother inclined her head modestly.

'That's so kind of you,' I told her. 'Thank you so much.'

Mrs Stephens beamed. 'You're very welcome, Ali. I'm glad to have had the chance to put my old skills to some use. It's good to know that I can still make a decent roast dinner.'

I kept smiling and went back to eating my chicken, thinking. Old skills, Mrs Stephens had said, and still. From those words and the envious glances my dinner was still getting from other people at the table it seemed that some members of the Stephens clan hadn't always suffered from the family "digestive peculiarities." I wondered what sort of unfortunate disease or gut condition could cause someone's body to change that way – and how I would manage if I was only able to eat soup for the rest of my life. I stole a glance to my left at Mrs Stephens' bowl: the contents were a deep brownish purple colour – beetroot or something, I supposed. The soup certainly didn't look as appealing as my chicken. Also, unlike my plate, no steam rose from the bowl: I think the soup might even have been cold.

'So Ali,' said Julia's grandmother, bringing my train of thought to a screeching halt. 'What do you want to do with your life?'

The old lady who'd been introduced to me as "Grandmama" was sitting in her wheelchair on my right, at the head of the table. Something in her looks told me she was Mr Stephens' mother, not Mrs Stephens': her face was square and solid and three very long thick black hairs sprouted from a large brown mole on her left cheek, but she was smiling and her eyes were bright. She looked friendly enough.

'I'd like to go into computer security,' I said. 'Protecting vulnerable systems from hackers and viruses.'

Julia and I had been seated separately: she was sitting about halfway along the table on the opposite side from me. I looked over at her for the slightly weary smirk on her face that was always her reaction to my career plans – and I felt oddly comforted and reassured when I found it.

'I know it's maybe not the most glamorous or exciting job on the planet,' I went on, 'but I think it's fun. Seriously. It's always changing, always about adapting to new challenges – and I think it'll be steady work, too. Banks, energy companies, even governments all depend on secure computer networks.'

I smiled at Julia. She smiled back encouragingly.

'Also,' I added, 'Julia and I should be able to do a bit of travelling – get to see what it's like to live in different countries. It's the kind of job that can take you around the world if you want it to.'

'But what about family?' asked Grandmama.

Her smile had dropped. Her eyes stared straight into mine. I realised it was time to tread carefully.

'My own family… aren't close,' I said. 'My folks split up when I was nine. My older sister went to live with my dad. I stayed with Mum.'

'What about cousins?' asked Mr Stephens.

Conscious I was surrounded by a tableful of cousins, I said: 'There are some aunties and uncles, mostly on my mum's side, but… we don't see each other much.'

Mr Stephens frowned. 'Why not?'

'To be honest,' I said, 'we don't really get on.'

There was a short pause.

'Well,' said Grandmama, 'it's all right, Ali. We're your family now.' Grinning at me she laid a liver-spotted hand on my right thigh and squeezed.

On the surface, some people might consider what she'd said to be charming and sweet: somehow I'd met with Grandmama's approval and now she was welcoming me into the clan. But that wasn't how I felt. There was a strange sort of trickling feeling in my stomach that had nothing to do with food: I felt threatened. I smiled back at her weakly.

Mr Stephens put his spoon down and dabbed at his lips.

'Hear, hear, Grandmama!' he said, and looked at me. 'Ali, we would be honoured to welcome you as one of the family.'

'Thank you,' I said. 'That's-'

He held up a hand. 'Before we do, there's a little ritual we would like you to take part in. It's a family tradition: a symbolic gesture to celebrate the fact that from tonight onwards you're going to be one of us. You agree?'

I looked at Julia. She caught my eye and gave a tiny but unmistakable shake of her head. I blinked again, astonished.

Julia wanted me to say no. But how could I? How could I possibly say no without insulting her entire family? I looked at Mr Stephens, who was still waiting for my answer.

'Sure,' I said. 'I mean: Yes.'

'Excellent. Please excuse me for a moment.' Mr Stephens rose to his feet and left the room. Nonplussed, I looked back at Julia again. Now she was mouthing words at me.

I watched her lips, trying to make out what she was trying to tell me. The message was short, just two words, but not being much of a lip-reader I didn't have the faintest idea what they were. As subtly as I could I shrugged – but the movement obviously wasn't subtle enough because Julia's sister Jennifer stopped watching me and turned sharply to look at Julia too. Julia looked down at her soup.

Mr Stephens came back carrying a large and impressive ceremonial tankard made of brightly polished silver with a lid on it, hinged at the top of its handle. He stood behind my chair. I had to turn in my seat to look up at him.

'This,' he said, holding the tankard in both hands, 'is what we call our Loving Cup. We will now all drink from it, to show we are all one family.'

He offered the tankard to Mrs Stephens who lifted the lid and raised the tankard to her lips.

'To family,' she said, and drank.

The gleaming silver tankard was so big that Julia's mother's face, already partially covered by her black bonnet, almost disappeared completely. After a moment Mrs Stephens lowered the tankard, closed the lid, and passed it along to her neighbour to her left – cousin Jerome, I think it was. He silently took a drink from the tankard, then passed it along to his neighbour, cousin Katherine. She took her turn, passed it on, and so on. I watched as the tankard made its way up one side of the table then down the other.

There was something terrible about the inevitability of the way the tankard was coming back towards me. A part of me was wondering what it contained; another part of me, frankly, was thinking about backwash and how much there would be in the tankard once all of the Stephenses had drunk from it. I could see why the Loving Cup ritual was significant: I was about to become a lot more intimate with the family than I was comfortable with. Meanwhile Julia was still trying to catch my eye, still mouthing the same two words from before. She was shaking her head: I'd pretty much identified the first word as "don't," but the second still wasn't clear. I kept getting distracted by the way each member of the Stephens family eyed me over the rim of the tankard as they took their turn to drink.

At last Mr Stephens took his turn, then Grandmama took hers and handed the tankard to me.

'There you are, Ali,' said Mr Stephens. 'Go ahead. Drink.'

What is it? I wanted to ask, or Can I have my own cup, please? But of course I couldn't. The family had welcomed me. If I didn't do exactly what they were expecting they would be insulted.

I made a lame attempt at a "cheers" gesture with the tankard then opened the lid. In the brief glimpse I got as I brought the brim to my lips I saw that the liquid inside was purplish red, wine of some kind I presumed – but as the stuff slid past my teeth and across my tongue I instantly realised it was like no wine I'd ever tasted. Thick and raw and earthy, it left a tingling numbness at the back of my throat as I swallowed it. Then, of course, I worked out the second word of Julia's message: don't swallow. I lowered the Loving Cup and saw that Mr Stephens was smiling at me.

I felt the liquid trace icy fingers down the inside of my chest. As it reached my stomach something strange happened: the sudden twist of panic that had formed there when I'd understood Julia's warning just as suddenly unravelled and went away. A warm, fuzzy glow began to spread outwards through my body.

'Please,' said Mr Stephens, 'have some more.'

I did.

It was very kind of Mr Stephens (I decided, drinking) to be so generous. In fact I suddenly felt enormously impressed and touched by the hospitable way I'd been treated by the whole Stephens family. It wasn't just the chicken; it wasn't the Loving Cup and what it contained, though whatever the liquid was (I reflected, gulping more) it was definitely extremely special and delicious and good. No: what got to me most at that moment was the way that the Stephenses had opened up to me. They'd let me in, accepted me as one of their own without prejudice or preconditions – me, an outsider, someone they'd barely met. Surely the trust they'd shown me deserved my trust in return. After all, they might be strange but - like I'd told Julia in the car - all families are weird.

'What's more important than family, Ali?' asked Mr Stephens, while I continued to drink.

'Nothing,' he answered for me, kindly, so I didn't have to stop. 'Nothing's more important than family.'

I swallowed the last of the liquid. I tipped back the tankard hoping for more but it was all gone. Very carefully and almost soundlessly except for a clank when my hand shook, I set the tankard back on the table.

Then I began to feel strange. There were purple-brown shadows at the corners of my eyesight. There was a high, piping whistle in my ears. My mouth started watering furiously and I was suddenly and horribly afraid I was going to be sick.

'Excuse me,' I said, getting to my feet, then grabbing the chair-back as I nearly fell over. 'I'm just…' I looked for the rest of what I'd been trying to say, but it wasn't there. 'I'll be right back,' I improvised. Then I headed for the doors.

'Ali!' Someone was shaking me. 'Ali, wake up!'

I was lying on a bed. It was the softest, most comfortable bed I'd ever slept on. It felt wonderful, and I was particularly delighted to be lying on it because I had no memory whatsoever of how I'd got there. My only wish was that whoever was shaking me would stop so I could go back to sleep: for a moment, as if in answer to my wish, the shaking did stop. But then Julia slapped me across the face.

'Ow! Julia, what do you want?'

'Get up,' she told me in a hoarse whisper. 'We've got to get out of here, right now.'

We were in the red room. I was on the four-poster bed, on top of the covers, with all my clothes on. Beyond the velvet curtains, which were open, I could see a full moon. That was the only light in the room.

'How long have I been asleep?' I asked, rubbing my eyes.

'You're lucky to wake up,' hissed Julia. 'What were you thinking? Didn't you see me trying to tell you not to drink it?'

'Julia,' I asked aloud, 'why are you whispering?'

'Will you be quiet and listen to me?' she rasped. 'You're in danger.'

I looked at her. My head was throbbing. My throat was parched. I couldn't smell vomit in the room, but – as I was uncomfortably aware – that didn't necessarily mean that I hadn't been sick somewhere anyway. I certainly remembered wanting to be sick, and didn't remember visiting a toilet.

'The Loving Cup,' said Julia. 'I didn't think they'd use it on you. I thought that once I'd had a chance to talk to them they might have let us go with a blessing or something – but they want you, Ali. They won't let us be together until you're one of us, and then we'll never be free of them. Oh Ali, what have we done?'

Silhouetted against the moonlight through the window, Julia's shoulders started to shake. I sat up and put my arms around her. Her face was wet.

'Ssshhh,' I told her, stroking her head, 'it's all right.'

'No,' she said firmly, pulling away. 'It isn't. Now come on, get up. We're leaving.'

The knock at the door almost gave me a heart attack.

'Ali?' said Jennifer's voice. 'Ali? Are you awake?'

Obviously not wanting to take a chance with mouthing the words this time, Julia put her lips to my ear. 'Answer her,' she breathed. 'Play for time.'

I stared at her, but she was already off the bed and moving. With impressive stealth Julia picked up a chair and carefully, silently, wedged it under the bedroom doorknob. 'Um, hello?' I called. 'Is that Jennifer?'

'Hi, Ali,' said Jennifer. 'I've been sent to let you know that the family is waiting for you. Are you ready to come back down?'

'Erm, just a second.'

Now Julia was doing something even more surprising. She'd gone to the window: after a brief struggle with the latch and an unbelievably loud squeal of protesting woodwork she'd opened it. She jerked her thumb at the moonlit night outside and put her mouth to my ear again.

'Climb down,' she breathed. 'Start running. I'll be right behind you. We'll get in the car and we'll go and we'll never come back.' She kissed me hard on the lips, then pushed me towards the window. 'Go on. Go!'

I looked at her. I looked at the window.

Then I walked to the door, took the chair out of the way, and opened it.

'Ali…' said Julia. 'Stop! You don't know what you're doing!'

Two of the beefier male cousins were standing at the door to either side of Jennifer. I was pleased to find that I remembered their names: cousin Rafe and cousin Caleb. I was very touched that they'd all come to help collect me. Smiling, I walked towards them.

'Ali, don't go with them!' said Julia. 'Ali! Stop! Please!'

'Come now, sister,' said Jennifer, with a disapproving look. 'Don't make this harder on poor Ali than it needs to be.'

'ALI!' Julia screamed, but the door to the red room clicked shut.

Cousin Rafe and cousin Caleb stood guard in front of it while Jennifer led me back down the stairs to the entrance hall.

There they were again: the family, looking up at me, waiting. In front of them, naked from the waist up, stood Mr Stephens.

Mr Stephens was very hairy. Long black hairs like spiders' legs sprouted from the sides of his biceps and across the tops of his shoulders. His torso, too, was a mass of black curls – all except for a long, thin patch of bare, white flesh that ran down the centre of his chest, down his sternum.

'Hello Ali,' Mr Stephens said, then: 'Help him take his shirt off.'

While I just stood there staring, cousin Malcolm and cousin Jerome stepped forward. They were clumsy and rough and some of my buttons burst, but I didn't care. I couldn't take my eyes off the strip of white flesh on Mr Stephens' chest.

It looked a bit like an operation scar. But it was moving. There was a ripple, as if something was pushing at the scar from behind – then the pale, shiny tissue was suddenly parting up the centre as if being unzipped.

Mr Stephen's chest opened like a vertical mouth, a bloodless ruby red wound. The skin of his torso stretched and wrinkled as his ribs swung back, exposing inside him a nest of pulsing, wriggling things. He held his arms out towards me.

'The family accepts you, Ali,' he said. 'Will you accept us?'

I couldn't speak. But I nodded.

'Then come to me.'

I did, and Mr Stephens hugged me.

I felt the rough warmth of his cheek against mine. I felt loved and cherished and safe. His arms tightened. The things inside him butted and strained at me. Then, with a feeling of release, they pushed through.

'Welcome to the family,' said Mr Stephens into my ear.

'Thank you,' I whispered.

Story © Sam Enthoven / Art © Laura Trinder, 2015. All Rights Reserved.

More bonus stories by Sam: Jethro’s Ace of Hearts, Tongues and Other Parts, The New Deal